During my previous semester at NHL Stenden Hogeschool we were required to work on a robotics project in groups. While a student project, it is still a project that I am proud of. Because of that I wanted to build an interactive page showcasing some of the engineering challenges faced in this small project.

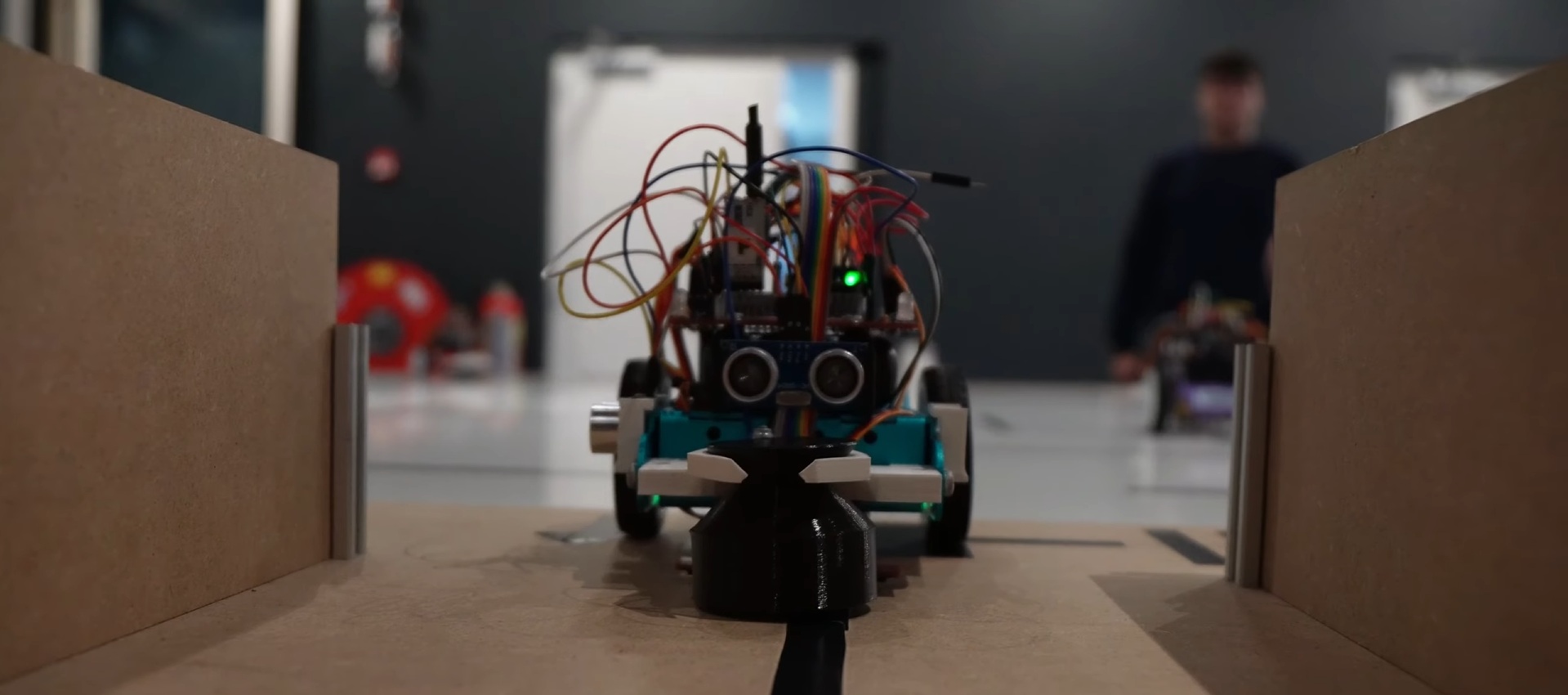

Each robotics team was required to program three different robots that would run one section of a racetrack, a competition to see who could produce the quickest run. The first stage required simply following a line, the second involved navigating a maze of lines, and the third involved navigating a physical maze with wooden walls.

This project was an opportunity for me to get more experience leading a team. My group had elected me leader due to my experience and communication skills. Our group managed to win first place in the relay race with all three courses performing well.

The stage that I personally worked on was the physical maze solving portion. During our final race, our maze solving robot was able to fully navigate the maze without any human intervention. This webpage will take you through how this project was engineered and what goes into a maze navigating robot.

Technical Design

Attending an undergraduate course as someone who has over a decade of experience programming meant I could choose to take it easy. I didn’t want to do that; I believe that you get out whatever you put in. So, I wanted to really consider my engineering choices and to ensure that I had good fundamentals.

To describe our code’s architecture in a simple manner. We have separate files with self-contained code for each sensor and actuator. This code was designed to not rely on other code in the system. This made code easy to develop as each component could be treated individually, making work easier. Additionally, it would speed up development of any other projects using those same sensors in the future.

The main code for the robot centers around what’s called Finite State Machine. A Finite State Machine consists of several states that the robot goes into. We then transition between these states according to certain rules. Transitions can be triggered under certain conditions and through this chain of events allows the robot to move intelligently through the maze.

Finite State Machine

Smooth High-Speed Navigation

How do you steer an autonomous vehicle? If our goal is simply to follow a line, we can do it easily. Simply turn right when we’re on the left of the line, and right when we’re on the right of the line. This primitive method of control works, but it’s not smooth, and it’s not reliable.

Instead, we needed something a little more sophisticated. So, we start by measuring how far away we are from where we want to be. This is called error. We can then use this error to determine not just what direction to steer, but how much to steer. This is a lot better than the all-or-nothing, “bang-bang”, control that preceded it. The specific controller we decided to implement is a PID controller, which operates on three simple rules.

The Three Rules of PID Control

1. Proportional (P): "If I'm further away from the line, I need to turn more."

2. Derivative (D): "If my error changes suddenly, I need to counteract the first rule."

If the robot rushes toward the line too quickly, this rule prevents it from overshooting

3. Integral (I): "If I'm consistently offset from the line, I need to account for that."

If there is something wrong with the robot, such as a motor being weaker, this will handle those unchanging errors.

Try Tuning a PID

How does the robot stay on the line? It uses a PID controller to constantly adjust steering. Try adjusting the gains below to see how they affect stability!

Proportional: Corrects error instantly. Derivative: Dampens oscillation. Integral: Fixes long-term drift.

Hardware Customization

In this relay race we were allowed to customize our robot’s hardware within reason. This is where we were able to differentiate our robot from others. To improve the robot’s ability to navigate the maze, we decided to add a gyroscope, an LSM6DS IMU. (Inertial Measurement Unit)

A gyroscope measures the rotational velocity of the sensor. This means it doesn’t know where it is, only how fast it moves. However, this knowledge is not enough to figure out what orientation the gyroscope is in. We can accurately figure out exactly how much pitch and role the robot has by measuring gravity as a reference direction. However, this means that yaw, where gravity feels the same no matter what the orientation, is not as accurate. Dealing with this drift was the primary engineering challenge to successfully implementing a gyroscope.

We can easily improve this by measuring relative to the starting orientation. But even then, our gyroscope was cheap, and inaccurate, so we had a lot of noise to deal with. We attempted to deal with this noise first by measuring the average and subtracting that from the reading. We could call that calibration.

However, this doesn't fully solve the calibration problem because we didn’t make the noise go away. As time goes on it will slowly drift away from the actual orientation. In the final implementation, gyroscope heading was reset during left turns. Left turns were chosen as they were most consistently at a measurable angle.

Gyroscope Drift

Gyroscopes drift over time due to sensor bias and noise. The robot must calibrate at startup to estimate this bias.

The Bigger System

The robot wasn't only self contained, rather it needed to communicate via wireless serial to the other robots. Since it was a relay race, each robot was required to hand off a baton to the next. Upon delivery, a message needed to be sent to signal the next robot to move.

A "base station" acted as a server and final authority in these wireless communications. This base station, managed the transitions between robots, including handling acknowledgements: short messages that were used to verify that each message was received by their target.

The wireless serial band that the robots were communicating over was only able to support a single robot "talking" at a time. If multiple were to talk at the same time, they would corrupt the sent data. This is why it's important that the base station handles these handshakes."

Network Communication Flow

Conclusion

I wanted to feature this project on my portfolio because it's something that I worked on recently, and because I wanted to present the process of building this robot in an interactive manner. I believe that presenting a user with a unique and interactive experience showcasing concepts in intuitive ways is an underrated aspect of software development.